How noise pollution quietly affects your health

Researchers have been sounding the alarm about noise pollution for decades, so why is it still such a big problem?

Quick Summary

- Environmental noise pollution is unwanted or harmful outdoor sound created by human activities, including noise from road traffic, railway traffic, airports, and industrial sites in which people are exposed involuntarily.

- This article covers current research on noise pollution, its impact on health, and future public health policy directions.

Whether you live deep in the country or in the heart of a bustling city, the relentless hum of modern life is as constant as the nonstop, digital cacophony that bombards the senses and demands our continual attention. So it's little wonder that one of the most pervasive environmental threats today — noise pollution — has managed to slip largely under the radar. We’ve tuned it out.

But noise pollution has long been considered a health hazard globally, with a large body of evidence linking noise to various health effects including sleep disturbance, learning, hypertension, and heart disease. It may affect mental health, and can lead to conditions like takotsubo cardiomyopathy aka "broken heart syndrome," an acute type of heart failure related to chronic stress that activates the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary (HPA) axis.

In 1981, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported that half the US population lived in areas with traffic noise from road, rail, or air significant enough to cause health problems. More recently, researchers in the European Union identified traffic noise as the second leading cause of environmental health risk after air pollution — contributing to a loss of 1 million life years annually, according to the World Health Organization.

The potential impact on children could be serious because evidence shows that once exposed to excessive noise, the body may overreact with repeated exposures, amplifying the negative effects. In kids, noise can increase psychological stress, raise blood pressure, and decrease overall quality of life. And it could affect learning by increasing hyperactivity and lowering reading scores.

In the US, there are significant disparities in who is exposed to noise pollution. Twelve percent of the US population is affected by jet noise, with people living near airports tending to come from communities with low socioeconomic status who are racial and ethnic minorities, a phenomenon related to longstanding housing and land use policies.

Noise may have far-reaching impacts beyond humans as well. Anthropogenic noise from low-flying airplanes, watercraft, oil and gas exploration, sonar, and seismic surveys can affect animals. Co-existence with human-made noise pollution impacts the reproductive success and migration of wildlife, lowering populations and increasing mortality.

“So many of us are chronically exposed to high levels of noise,” says Peter James, PhD, Director of the UC Davis Center for Occupational and Environmental Health. And while research on noise pollution is more urgent than ever, James says it faces certain challenges, too.

“Federal policy doesn’t support systematic noise modeling so it’s difficult to conduct epidemiological research on the health effects of noise,” says James. “With standardized and improved exposure modeling, we could more precisely impact the health effects of noise and target potential interventions to reduce noise exposure.”

What the Latest Research Says About Noise Pollution

In the past, noise pollution research focused on trains, planes, and automobiles. When people thought of the way noise related to their health, hearing loss was likely the first thing that came to mind. But newer research shows there may be long-lasting health effects that go beyond the impact on the ears.

Heart & Cardiovascular Impacts

Long-term noise exposure is associated with cardiovascular events like heart attacks and strokes. Most research has focused on traffic noise. Newer research is looking at the ways chronic noise affects chronic disease.

- Looking at the broader range of noise pollution – road, aircraft, railway, occupational, combined transportation, and other varied sources – a 2023 study of meta-analyses and systematic reviews found cardiovascular outcomes were associated with all noise types except for railway noise.

- A 2023 study analyzed long-term exposure to man-made noise — both day and night — in more than 114,000 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study. Researchers linked health outcomes to acoustic data from hundreds of urban and rural US communities. They found a small association between outdoor noise and the risk of heart attacks and strokes, and that nighttime noise had a stronger association with heart disease than with stroke overall. While the combined risk for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes was not statistically significant, there was a notable positive association between nighttime noise and hemorrhagic stroke — an effect that was also observed during the daytime.

- A 2024 Harvard University study analyzed the deaths of almost 1 million people across five states and found a link between cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and exposure to noise from humans related to industrial, commercial, and community activities. Researchers linked CVD deaths to noise at night as well as during the day and found a stronger association in women.

Sleep & Mental Health Impacts

Noise activates the sympathetic nervous system, leading to fragmented sleep and reduced total sleep time. Among adolescents, later bedtimes have been linked to poorer mental health, increased substance use, and lower academic performance.

- A 2019 systematic review analyzed results from several studies on the association between transportation noise and behavioral and emotional disorders in children and adolescents. The meta-analysis found that odds of hyperactivity, inattention and total difficulties significantly increased 9 to 11 percent with 10 decibels of road traffic noise.

- In a first-of-its-kind study in 2019 on anthropogenic noise, sleep, and mental health outcomes in more than 4,500 adolescents, researchers assessed the impact of nighttime urban noise across the US. Nearly 71% of adolescents in the study lived in high-noise areas in urban environments, which also typically had higher levels of schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression. The study found that higher environmental noise exposure was associated with later bedtimes, but not total hours slept. Associations between noise exposure and mental health outcomes like depression and anxiety were less consistent, with some links to inattention and hyperactivity but not to diagnostic-level mental health disorders.

Noise Pollution Types and How They Harm Us

While researchers are learning that chronic noise can affect whole body systems, they’re also discovering that different types of sound can have an impact on the body in more nuanced ways. From the hum of the freeway in your backyard that’s so loud you raise your voice to be heard, to the sudden high-pitched blast of a guitar from the speaker you’re standing next to at a concert, noise can harm in a multitude of ways.

Exposure to loud noise kills nerve endings in the inner ear, with repeated exposure amplifying their destruction. This type of injury causes Noise Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL) by limiting the ability to hear high frequency sounds. NIHL is permanent and can’t be corrected through surgery or other medical interventions, so prevention is the key.

Chronic exposure to lower-level noise — like the ambient sounds of a freeway — as well as direct high-level noise associated with hearing loss — like the sudden thunder of a guitar — elicit a similar stress response in the brain. This response activates the HPA axis, which in turn can lead to feelings of fear and anxiety and inflammation in the body.

Research also shows sound variation can be harmful, even when decibel averages are the same. Over the course of a night, a train and highway may average the same decibel levels, but the fluctuation of intensity of train noise may be particularly dangerous to your health. Researchers have associated “noise intermittency” – those loud punctuations of sound amid softer background noise – with heart disease, heart attacks, heart failure, and stroke.

But association is not cause. “There is much we still don’t know about noise exposure, and intermittent noise is even more complex to model,” says James. “Without better systematic and nationwide measurement of noise — similar to our air pollution monitoring network — we won’t be able to tease out the health effects of noise exposure.”

Noise Policy Progress and Gaps

The US government first recognized noise as a public health issue in 1968, and more than half a century later, a lack of consensus at every level — from research to policy to political will – has meant noise pollution is still a major public health threat. Despite decades of research on the health effects of environmental noise pollution, the United States doesn’t have a national plan to curtail it, and statewide legislation has yet to fix it.

Some of this disconnect is related to research and the different ways data is interpreted. Noise is harder to quantify in research than air and water pollution, can’t be tasted, seen, or smelled, and is highly variable. Noise is a perception received by the brain, which interprets the same noise at the same level differently depending on time of day and where it’s coming from and may vary from person-to-person. Even at the same intensity, research shows noise from airplanes is more irritating than noise from roadway and rail traffic, making it highly individual.

There is also a lack of alignment among researchers on methodology, measurement, and endpoints, which makes it difficult to draw comparisons between populations. Research interpretations in Europe typically involve mental health, which contrasts with research in the US that’s more focused on disease.

Data at odds with itself has made it harder for policymakers to develop a holistic response. Research on noise pollution and stroke, for example, has historically relied on inconsistent data from the EU and limited US-based studies — particularly on nighttime anthropogenic noise. This gap has made it harder to inform policy in the US and craft effective regulations, even though scientists have long hypothesized that nighttime noise may be more harmful due to its disruption of sleep.

Noise Legislation in the United States

The first federal agency to enact a noise policy in the US was the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) through its 1969 Noise Standards Certification, but its scope was limited to certain types of aircraft.

OSHA passed its first noise policy in 1971. OSHA’s Noise Exposure Regulation helped protect, test, and train workers against hearing loss.

Noise control and abatement policies that related more broadly to public health came with the passage of the EPA’s Noise Control Act of 1972, which together with the Quiet Communities Act of 1978, regulated noise sources from traffic, low-noise emission products, construction equipment, transport equipment, trucks, motorcycles, and the labeling of hearing protection devices.

In the early days, the EPA’s federal policy identified noise levels to protect public health, labeled noisy consumer products like lawnmowers, chainsaws, and motorcycles, and paid for research that set noise standards for traffic sources. One of its big achievements occurred in 1975 when US commercial air carriers had to retrofit thousands of airplanes with new engine housings lined with sound absorbing material.

The FAA’s first comprehensive set of regulations was the Aviation Noise Abatement Policy of 1976. During this time, the FAA established its framework to adopt more stringent noise standards by working with manufacturers to build quieter airframes and powerplants, which the agency says has been the single most important factor in decreasing noise pollution from planes.

All of this was great progress until the Reagan Administration defunded the EPA’s noise program and completely phased out its Office of Noise Abatement and Control in 1982, which shifted primary responsibility of regulating noise pollution to state and local governments.

California enacted its own comprehensive policy through its Noise Control Act of 1973 and as a result currently has some of the most stringent noise abatement policies in the country.

Today, California’s Health and Safety Code 46000 ensures residents are entitled to “a peaceful and quiet environment without the intrusion of noise which may be hazardous to their health or welfare.” But interpretation and enforcement has been left to local governments, so policies and efficacy in curtailing noise pollution vary greatly, depending on where you live.

To understand how different communities deal with noise, compare Palms Springs's stringent noise ordinances with Sacramento's.

A Call for Noise Pollution Solutions

Everyday environmental noise is getting louder and increasingly problematic. More the half the world’s population currently lives in an urban area, according to the United Nations. By 2050, that number is expected to grow to 70 percent. As more people crowd together, anthropogenic noise will likely get worse and more difficult to mitigate.

What’s needed now more than ever is the political capital and will to change how we live with noise. While California has a plethora of noise pollution regulations on the books affecting transportation, aircraft, freeway, housing, construction, and other types of noise, every challenge and rollback proves regulations are not enough. Alignment on what noise pollution is and how it harms us is the foundation needed to build for real change.

“Without effective policy and funding for research on the health effects of noise, it’s unlikely we will move the needle to decrease noise exposures in this country,” says James. “With growing evidence that noise may impact multiple health outcomes, we need to act now to model noise exposures, quantify their impacts on human health, and develop interventions to decrease exposure.”

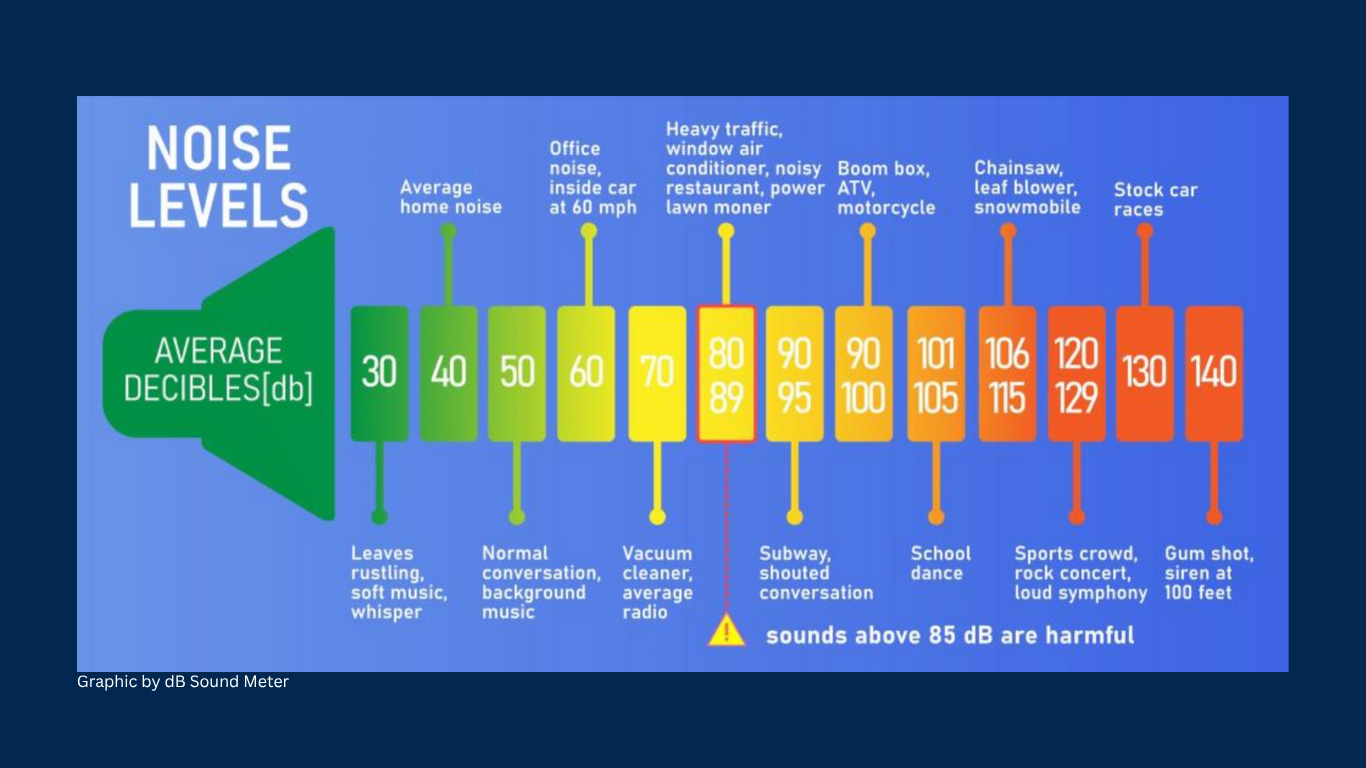

When is Noise Too Loud?

A single exposure to intense noise or a steady, long-term exposure can result in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss.

In the United States, the EPA says keeping intermittent noise below 70 decibels is required to prevent hearing loss. And the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers have a hearing conservation program in place if workers’ average exposure is 85 decibels or higher over 8 hours. OSHA’s general guidance is if you have to raise your voice to speak to someone who’s 3 feet away, the noise level could be above 85 decibels.

To learn more about noise levels, try downloading the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health's sound level meter. Developed by sound engineers and hearing loss experts, it has a hazardous noise level guide and provides accurate measurements. It's free and works on any IOS device.

Jennifer Biddle is a health and science writer, editor, and video producer at the UC Davis School of Medicine.

Media Resources

Source List

- Noise as a Public Health Hazard. American Public Health Association. Published October 25, 2021. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2022/01/07/noise-as-a-public-health-hazard

- The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. Noise pollution: more attention is needed. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2023;24:100577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100577

- OSHA. 1910.95 - Occupational noise exposure. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Osha.gov. Published 2019. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.95

- OSHA. Occupational Noise Exposure - Overview | Occupational Safety and Health Administration. www.osha.gov. Published 2023. https://www.osha.gov/noise

- Hammer MS, Swinburn TK, Neitzel RL. Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122(2):115-119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307272

- Al Houri HN, Jomaa S, Jabra M, Alhouri AN, Latifeh Y. Pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive literature review. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022;82:104671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104671

- Hänninen O, Knol AB, Jantunen M, et al. Environmental Burden of Disease in Europe: Assessing Nine Risk Factors in Six Countries. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122(5):439-446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1206154

- The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. Noise pollution: more attention is needed. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2023;24:100577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100577

- Evans GW, Bullinger M, Hygge S. Chronic Noise Exposure and Physiological Response: A Prospective Study of Children Living Under Environmental Stress. Psychological Science. 1998;9(1):75-77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00014

- Bronzaft AL, McCarthy DP. The Effect of Elevated Train Noise On Reading Ability. Environment and Behavior. 1975;7(4):517-528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657500700406

- Clark C, Head J, Haines M, van Kamp I, van Kempen E, Stansfeld SA. A meta-analysis of the association of aircraft noise at school on children’s reading comprehension and psychological health for use in health impact assessment. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2021;76:101646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101646

- Number of People Residing in Areas of Significant Noise Exposure Around U.S. Airports | Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Bts.gov. Published 2020. https://www.bts.gov/content/number-people-residing-areas-significant-noise-exposure-around-us-airports

- Simon MC, Hart JE, Levy JI, et al. Sociodemographic Patterns of Exposure to Civil Aircraft Noise in the United States. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2022;130(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp9307

- The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. Noise pollution: more attention is needed. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2023;24:100577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100577

- Roscoe C, Grady ST, Hart JE, et al. Association between Noise and Cardiovascular Disease in a Nationwide U.S. Prospective Cohort Study of Women Followed from 1988 to 2018. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2023;131(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp12906

- Chen X, Liu M, Zuo L, et al. Environmental noise exposure and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health. 2023;33(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad044

- Jin T, Kosheleva A, Castro E, Qiu X, James P, Schwartz J. Long-term noise exposures and cardiovascular diseases mortality: A study in 5 U.S. states. Environmental Research. 2024;245:118092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.118092

- Roscoe C, Grady ST, Hart JE, et al. Association between Noise and Cardiovascular Disease in a Nationwide U.S. Prospective Cohort Study of Women Followed from 1988 to 2018. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2023;131(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp12906

- Schubert M, Hegewald J, Freiberg A, et al. Behavioral and Emotional Disorders and Transportation Noise among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(18):3336. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183336

- Rudolph KE, Shev A, Paksarian D, et al. Environmental noise and sleep and mental health outcomes in a nationally representative sample of urban US adolescents. Environmental Epidemiology (Philadelphia, Pa). 2019;3(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/EE9.0000000000000056

- Evans GW, Bullinger M, Hygge S. Chronic Noise Exposure and Physiological Response: A Prospective Study of Children Living Under Environmental Stress. Psychological Science. 1998;9(1):75-77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00014

- OSHA. Occupational Noise Exposure - Overview | Occupational Safety and Health Administration. www.osha.gov. Published 2023. https://www.osha.gov/noise

- Hahad O, Kuntic M, Al-Kindi S, et al. Noise and mental health: evidence, mechanisms, and consequences. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2024;35:1-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-024-00642-5

- Wunderli JM, Pieren R, Habermacher M, et al. Intermittency ratio: A metric reflecting short-term temporal variations of transportation noise exposure. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2015;26(6):575-585. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2015.56

- Vienneau D, Saucy A, Schäffer B, et al. Transportation noise exposure and cardiovascular mortality: 15-years of follow-up in a nationwide prospective cohort in Switzerland. Environment International. 2022;158:106974. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106974

- Wunderli JM, Pieren R, Habermacher M, et al. Intermittency ratio: A metric reflecting short-term temporal variations of transportation noise exposure. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2015;26(6):575-585. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2015.56

- Vienneau D, Saucy A, Schäffer B, et al. Transportation noise exposure and cardiovascular mortality: 15-years of follow-up in a nationwide prospective cohort in Switzerland. Environment International. 2022;158:106974. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106974

- Apolline Saucy, Beat Schäffer, Louise Tangermann, Danielle Vienneau, Jean-Marc Wunderli, Martin Röösli, Does night-time aircraft noise trigger mortality? A case-crossover study on 24 886 cardiovascular deaths, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 8, 21 February 2021, Pages 835–843, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa957

- Hammer MS, Swinburn TK, Neitzel RL. Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122(2):115-119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307272

- Noise as a Public Health Hazard. American Public Health Association. Published October 25, 2021. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2022/01/07/noise-as-a-public-health-hazard

- The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. Noise pollution: more attention is needed. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2023;24:100577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100577

- Borealisdev.net, Juneau M. Noise, a little-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease | Observatoire de la prévention de l’Institut de Cardiologie de Montréal. Observatoire de la prévention de l’Institut de Cardiologie de Montréal. Published September 15, 2023. https://observatoireprevention.org/en/2023/09/15/noise-a-little-known-risk-factor-for-cardiovascular-disease

- Hume KI. Noise Pollution: A Ubiquitous Unrecognized Disruptor of Sleep? Sleep. 2011;34(1):7-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.1.7

- Code of Federal Regulations. Part 36 Noise Standards: Aircraft Type and Airworthiness Certification. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-36

- Thunder TD. Hearing Conservation in the US: A Historical Perspective. AudiologyOnline. Published 2024. https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/hearing-conservation-in-us-historical-1263

- EPA. Clean Air Act Title IV - Noise Pollution | US EPA. US EPA. Published November 29, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/clean-air-act-title-iv-noise-pollution

- EPA. Office of Noise Abatement. Information on Levels of Environmental Noise Requisite to Protect Public Health and Welfare With an Adequate Margin. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/2000L3LN.PDF?Dockey=2000L3LN.PDF

- EPA. EPA Establishes New Noise Label Program. www.epa.gov. https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/aboutepa/epa-establishes-new-noise-label-program.html

- EPA. EPA History: Noise and the Noise Control Act | US EPA. US EPA. Published January 29, 2013. https://www.epa.gov/history/epa-history-noise-and-noise-control-act

- EPA. EPA Proposes Quieting of Jet Airplanes. www.epa.gov. https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/aboutepa/epa-proposes-quieting-jet-airplanes.html

- FAA. FAA History of Noise | Federal Aviation Administration. Faa.gov. Published 2022. https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/policy_guidance/noise/history

- Reagan Presidential Library. Environment: Noise. Box 79. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/public/2025-01/40-052-12006495-H79-002-2024.pdf

- Weinberg P. Masquerade for Privilege: Deregulation Undermining Environmental Protection. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=2365&context=wlulr

- EPA. EPA History: Noise and the Noise Control Act | US EPA. US EPA. Published January 29, 2013. https://www.epa.gov/history/epa-history-noise-and-noise-control-act

- Vankin J. The Art of Noise: Efforts to Manage Noise and Create a Quieter Environment, Explained. California Local. Published August 31, 2021. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://californialocal.com/localnews/statewide/ca/article/show/603-noise-pollution-explainer

- Shapiro, A. The Dormant Noise Control Act and Options to Abate Noise Pollution. Report to Administrative Conference of the United States. 1992. https://www.acus.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1992-06%20Implementation%20of%20the%20Noise%20Control%20Act.pdf

- California Code, HSC 46000. Ca.gov. Published 2025. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=HSC§ionNum=46000

- EPA. EPA History: Noise and the Noise Control Act | US EPA. US EPA. Published January 29, 2013. https://www.epa.gov/history/epa-history-noise-and-noise-control-act

- Jin T, Kosheleva A, Castro E, Qiu X, James P, Schwartz J. Long-term noise exposures and cardiovascular diseases mortality: A study in 5 U.S. states. Environmental Research. 2024;245:118092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.118092

- Christopher MZ Ben. As one more housing project stalls on noise concerns, another head sprouts from “CEQA Hydra.” CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/housing/2023/08/ceqa-noise-pollution/. Published August 17, 2023.